Note:

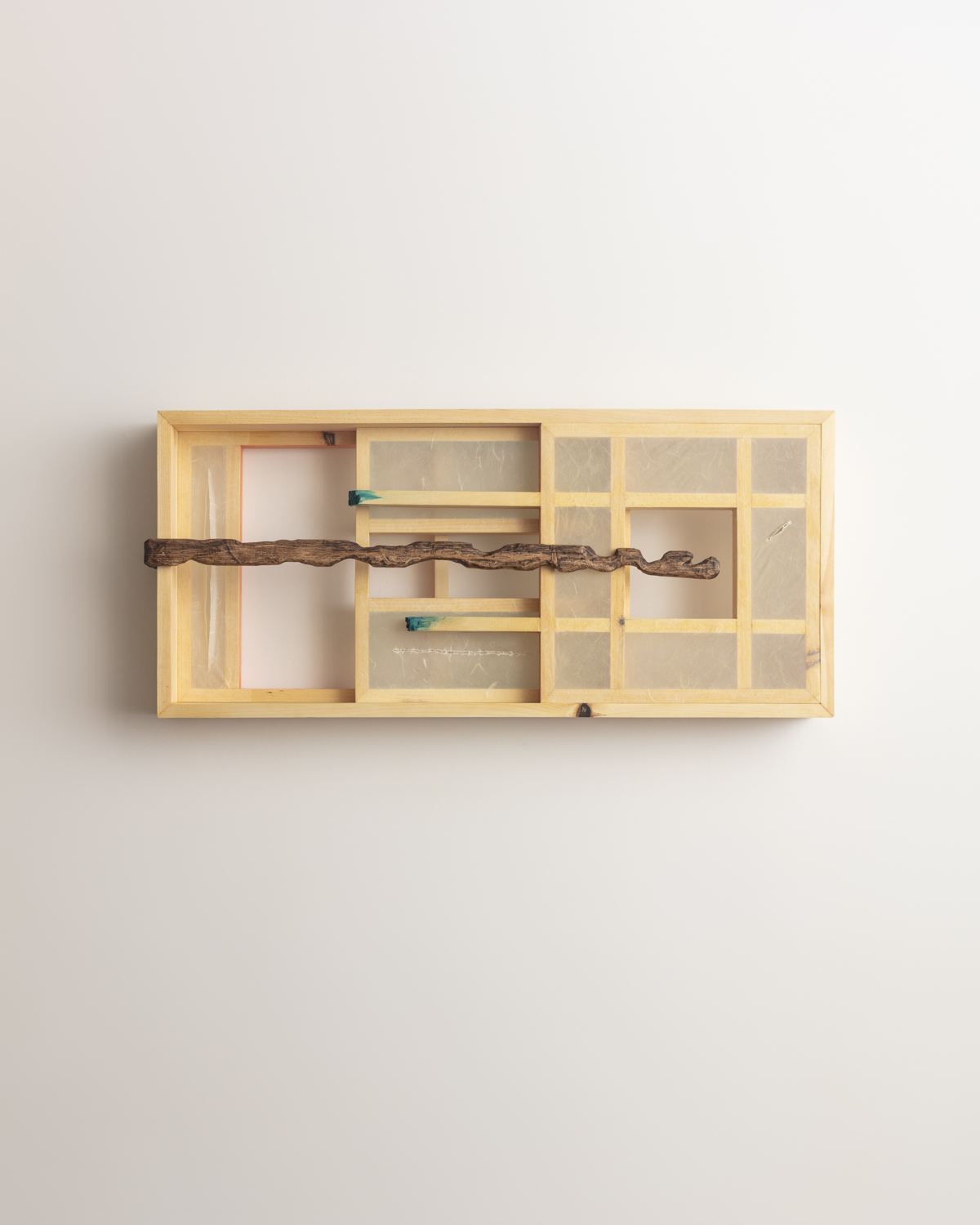

Jan 2026:My recent work approaches the window not as a metaphor for viewing, but as a condition—an unstable state that can slip, resist, or require intervention to remain in place. Using pinewood frames, hanji paper, and embedded light, I construct structures that hover between architecture and object, visibility and obstruction.

Rather than functioning as transparent devices, these windows behave unpredictably. Light is no longer external or given; it is held within the structure, delayed by layers of paper, or partially blocked by the frame itself. In this sense, perception is no longer passive. It becomes something shaped by friction, weight, and material resistance.

Hand-carved elements appear throughout the work as interruptions or braces—manual interventions that prevent the window from fully opening or collapsing. These gestures suggest acts of holding rather than revealing. The hand does not point outward; it stays with the structure, negotiating its balance and instability.

Across wall-mounted, leaning, and floor-based forms, the window repeatedly loses its fixed position. It tilts, braces itself, or appears overridden by its own support system. There is no clear distinction between inside and outside. Instead, the work remains suspended in an in-between state, where control is provisional and seeing is shaped by constraint rather than clarity.

Rather than resolving this tension, my practice stays with it. Fragility, weight, and containment are treated not as vulnerabilities, but as active forces—conditions that define how space is perceived, inhabited, and momentarily held together.

Aug 2025:

My work begins from the quiet space between seeing and being seen. I grew up surrounded by the soft opacity of hanji screens in Korea and the clarity of glass windows in the West—a duality that made me question what is meant to be visible, and what is meant to be sensed. This tension stayed with me. Over time, it grew into a desire to build not just images, but structures that hold memory, containment, and the possibility of crossing through.

I began carving pinewood into window-like frames and layering them with hanji, alcohol ink, and pastel washes. These materials are both fragile and persistent—like memories. The works are often openings, but not fully open; closures, but not fully shut. In Opening in Between, When I Opened the Window, or In the Pause Between, I trace a rhythm of hesitation, resistance, and reach. The carved forms—resembling hands or remnants of gestures—serve as quiet actors, holding, touching, or waiting at the edge of an unseen threshold.

This body of work is a response to living in-between languages, geographies, and expectations. As an immigrant and a maker, I find myself returning to boundaries—not to reinforce them, but to soften and question them. What happens if a window doesn't show the world, but instead reflects the quiet inside? What if the act of looking becomes an act of feeling?

Through these pieces, I invite viewers to stay in that in-between—to look, not for answers, but for a presence.

Apr 2025:

I begin by building a frame in an empty space.

I cut wood, draw lines, and divide the surface.

The grid doesn’t exist to convey meaning—

it’s a quiet rhythm, a way to hold still an uneasy space.

My background in graphic design taught me to fill fixed formats.

In photography and video, I had to create a frame around what refused to be held.

That repetition became exhausting.

Now, I try to create a place where things can simply remain—

without needing to be resolved.

I construct structures from pinewood,

divide them from within,

and layer hanji paper across the surface.

Hanji softens the light and blurs the gaze.

Red and green appear, but rarely collide.

They drift, pause, or remain uncertain.

Color doesn’t express emotion.

It only pretends to.

I rarely show my emotions.

Color becomes a quiet way to let something pass—

without saying too much.

Hands appear in my work.

They seem still, but they aren’t fixed.

They carry a kind of potential—

to reach or to retreat.

Suspended in between, they wait without conclusion.

The frame, to me, is both a way of seeing

and a way of holding myself together.

Inside it, I hide, empty out, and occasionally reveal.

For now, I remain somewhere in between.

Feb 2025:

A window is never just a window. It decides what we see and what remains hidden. In my work, I construct wooden frames that define a particular view, partially obscured by hanji paper. This thin yet significant barrier does not completely block the outside world but filters it—softening edges, diffusing light, leaving room for interpretation. Unlike glass, which promises clarity but reflects as much as it reveals, hanji offers a different way of seeing: one that embraces both ambiguity and presence.

Looking through a window is never passive. We believe we see the world as it is, but our vision is always framed—by culture, memory, and the structures that surround us. In my work, hands grip the frame, holding onto its edges, yet they cannot fully open or remove it. Does the frame offer protection, or does it confine? If the window were gone, would we see more, or would we be lost in formless space?

Western glass windows suggest transparency, an unobstructed truth, yet they also separate and contain. Traditional Korean hanji windows, by contrast, allow light and air to pass through, embracing the imperfect and the uncertain. My work exists between these two ideas—between clarity and concealment, between the seen and the imagined.

These frames do more than define a view; they shape perception itself. The world we see is never just what is there, but what is allowed, what is constructed, what is remembered. Through my work, I explore this tension—not just between inside and outside, but between choice and constraint, agency and illusion. What we believe to be an open view may, in the end, be nothing more than a carefully placed frame.